Scot HEYWOOD

Planar Variations

July 12 - September 1, 2023

Reception for the artist Wednesday, July 12, 6-8PM

-

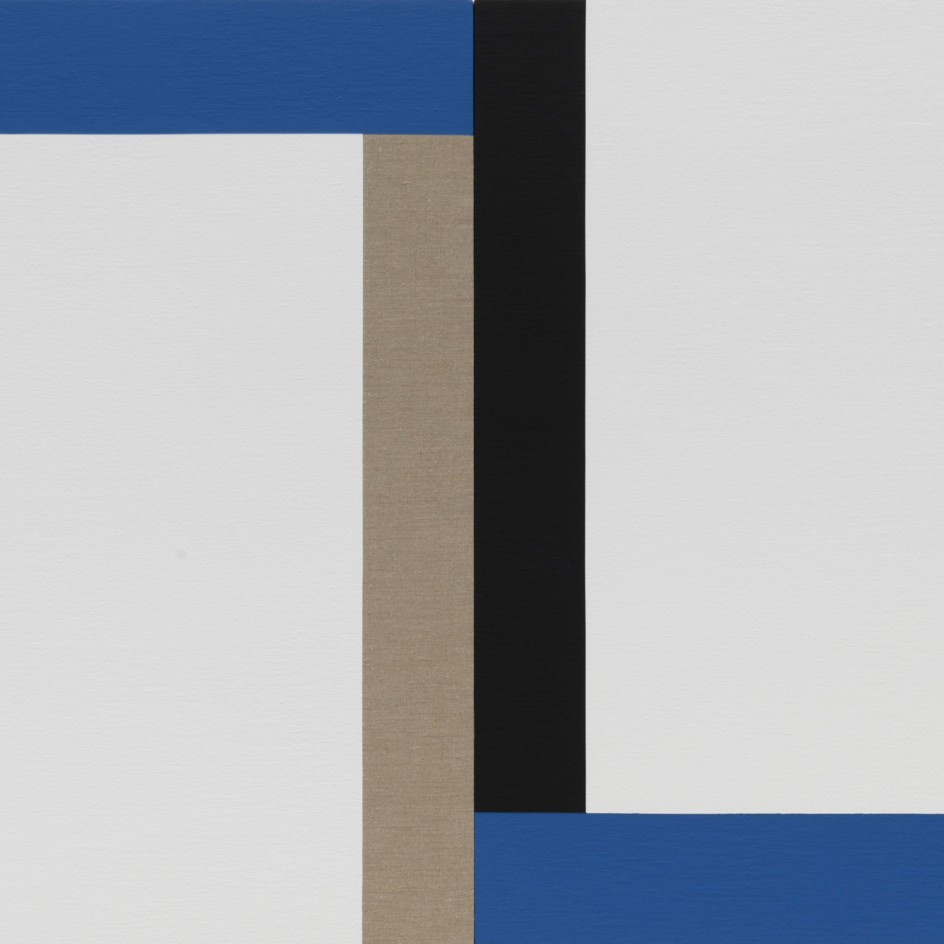

Matisse's Window – white, linen, black, blue

-

Double Edge – red, blue, yellow

-

Arupa – black, blue, canvas

-

Compression – gray, red, canvas

-

Arupa – yellow, gray, canvas

-

Transition – linen, black, gray, white

-

Arupa – gray, red, canvas

-

Double Edge – yellow, blue, gray

-

Haikube – linen, white, black

-

Haikube – red, black, gray, linen

-

Haikube – white, black, linen

-

Haikube – white, linen, grey

-

Haikube – black, linen, white

-

Haikube – white on white

Summary

From the day he first picked up a paintbrush, Scot Heywood knew exactly what he wanted to accomplish. Heywood has been single-mindedly focused for the past half century on “the experiential possibilities of a nonrepresentational geometric abstract painting.”

Although he was inspired by the pioneering abstraction of Kasimir Malevich and Piet Mondrian, Heywood came of age in 1970s Los Angeles, where masters such as John McLaughlin were perfecting a hard-edge aesthetic and fetish finish that would make Broadway Boogie Woogie seem figurative by comparison. Absorbing the work in his midst, including the emphatically nonrepresentational painting of contemporaries such as James Hayward, Edith Baumann, Ed Moses, Mary Corse, and John M. Miller, Heywood developed a unique approach that forefronts “the frontal nature of the painted plane, precognitive experience, and, ultimately, singularity.”

Like other painters of the period, he began his quest by creating monochromatic panels, modulating light in terms of the relationship between color and the painted surface. In this way, he effectively addressed Clement Greenberg’s 1961 assertion that “The first mark on a canvas destroys its literal and utter flatness,” which, Greenberg argued, led artists such as Mondrian to produce “a kind of illusion that suggests a kind of third dimension.”

However, it was an early accident that led to Heywood’s crucial breakthrough, distinguishing his work and establishing his future direction. While organizing monochrome paintings on his studio floor, he observed the chromatic relationship between them, and also noticed the lines made when they were set side-by-side. These marks were not illusionistic, but a consequence of the physicality of the canvases. Another physical parameter became apparent when he set the canvases on the wall and one of them slipped out of alignment. “Suddenly I had gravity,” he recalls. “Suddenly I had tension on an extreme level that I couldn’t get from lining them up evenly.”

With those compositional elements, together with his command of color and texture, Heywood had all he needed to explore the experiential possibilities of abstraction on his own highly personal terms. Ever since, it’s been a matter subtle incremental change. “It’s like a four- or five-year period and then – boom! – just a minor shift,” he says.

Modernism Gallery is pleased to present Planar Variations, featuring thirteen paintings created by Heywood between 2008 and 2020. The paintings all enlist Heywood’s multi-panel format to achieve tension and balance. Although they range in scale, their physical presence is always profound. They are all effectively architectural, the walls acting as a support for their visual structuring of the surrounding space and the viewer’s perceptual experience.

Heywood’s handling of gravity is a decisive factor. In paintings such as Double Edge – Yellow, Blue, Gray and Double Edge – Red, Blue, Yellow, he uses slippage of a panel to evoke a gravitational difference between different color weights.

The slippages also introduce physical asymmetries that, because the paintings are so perfectly balanced visually, make the room seem to tilt and torque. These effects are especially pronounced in his Haikube series.

Within each of his paintings, Piet Mondrian sought to achieve a quality he called “dynamic equilibrium.” Through his arrangement of multiple panels, Heywood takes dynamic equilibrium beyond the confines of the picture plane to include the space occupied by the viewer. Ultimately the dynamic equilibrium is kinesthetic, experienced in the spectator’s own body.

As Heywood explains, “The structural and coloristic intent is always directed towards a dynamic/static tension, forcing the viewer into not simply a conceptualization of the work, but one that allows for a physical relationship between viewer and painting.” The result is “a viewer-painting relationship that is direct, immediate, and timeless.”